The Astoria Theatre at 149-151 Charing Cross Road was one of the West End’s early ‘super cinemas’. It opened in 1927 on the site of a former factory owned by the condiment manufacturers Crosse and Blackwell, who had their head offices nearby in Soho Square.1 The factory, which was said to have ‘spread abroad fruity odours’ from jams and ‘the pungent smell of pickles’, had been an important source of employment for the working-class residents of Soho. It closed in 1921, when Crosse and Blackwell relocated their main works to a former machine-gun factory in Staffordshire.2

After the Crosse and Blackwell factory closed, developers approached the local authorities with various plans to transform the factory buildings into a theatre, dance hall or office block. Eventually, permission was given to build a cinema, with a dance hall at basement level and a row of shops facing out onto Charing Cross Road.3 Excavation and construction work for the project began in February 1926 and took nearly a year to complete.4 The architect, Edward A. Stone, who went on to design four more Astoria cinemas around London, chose a classical style for the building, with a domed turret over the entrance hall.5 But, like other big construction projects in London at the time, such as Adelaide House in the City and the ‘Oxo Tower’ on the Southbank, the Astoria also took advantage of very modern steel-framed building methods.6 The cinema opened to the public on 12 January 1927. Inside the auditorium, there was seating for around 2,000 people. When the dance hall opened a few days later, it accommodated another 1,000 patrons. In common with other 1920s ‘super cinemas’, like the Tivoli on the Strand and the Empire Theatre in Leicester Square, the building also included amenities such as a promenade and a restaurant. One journalist remarked that ‘the Astoria is a place where … one may spend a pleasant evening without seeing a picture!’7

After a year, the cinema was sold by the original backers, E.E. Lyons and H.T. Underwood, to the General Theatres Corporation (GTC) for over £250,000.8 It changed hands again a few months later, when GTC was taken over by the Gaumont-British Picture Corporation.9 This was part of the wider restructuring of the British film industry in the late 1920s, when production, distribution and exhibition companies began to merge to form large corporations, or ‘combines’, with their own nationwide cinema chains. The Astoria remained a popular part of West End nightlife into the 1930s.10 It closed as a cinema in the 1970s, and was demolished in 2009 as part of the construction of the Crossrail transport system.11

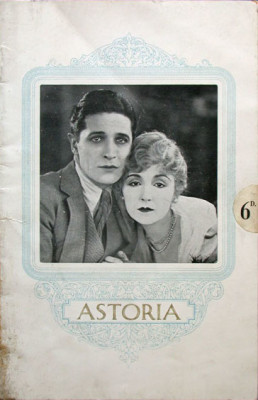

Image: Souvenir opening programme for the Astoria, 12 January 1927, showing Ivor Novello and Isabel Jeans. Credit: Courtesy of the Bill Douglas Cinema Museum, University of Exeter: www.bdcmuseum.org.uk.

Further reading:

- Allen Eyles with Keith Skone, London’s West End Cinemas, third edition (Swindon: English Heritage, 2014).

- Cathy Ross, Twenties London: A City in the Jazz Age (London: Museum of London/Wilson, 2003).

- Judith Walkowitz, Nights Out: Life in Cosmopolitan London (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012).

- J.H. Cardwell, et al, Two Centuries of Soho: Its Institutions, Firms, and Amusements (London: Truslove and Hanson, 1898), p. 205. ↩

- ‘Soho Jam Factory’, The Times, 25 February 1921, p. 7; Judith Summers, Soho: A History of London’s Most Colourful Neighbourhood (London: Bloomsbury, 1989), p. 161. ↩

- Building Act Case File (Cinemas), London Metropolitan Archives, GLC/AR/BR/7/3083/1, Astoria Dance Hall and Cinema. ↩

- ‘The Astoria’, Kinematograph Weekly, 13 January 1927, pp. 95-103. ↩

- ‘The Astoria Cinema and Dance Hall’, Architecture (September-October 1927), 26. ↩

- Cathy Ross, Twenties London: A City in the Jazz Age (London: Museum of London/Wilson, 2003), p. 119. ↩

- ‘London’s Newest Cinema’, Daily Express, 10 January 1917, p. 3. ↩

- ‘Theatre Sales. Big Price for a Cinema’, The Times, 18 January 1928, p. 10. ↩

- Allen Eyles with Keith Skone, London’s West End Cinemas, third edition (Swindon: English Heritage, 2014), p. 78. ↩

- See Judith Walkowitz, Nights Out: Life in Cosmopolitan London (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), pp. 183-90. ↩

- Eyles, London’s West End Cinemas, p. 80. ↩